We appreciate the artwork on an aesthetic level, but often the mastery of preservation and fine art restoration can be just as staggering in scale. That’s why this month’s Spotlight is being shone on Jackleen Leary of Fine Art Paper Restoration and Conservation, who displays technical prowess over the restoration of paper-based artworks. Our chat yielded valuable insight into the technical aspects of fine art creation and helped us gain a deeper appreciation for an artistic intention beyond the paint on a canvas.

How long have you worked with us?

Well, I have been working on projects with Armand Lee, Seaberg’s sister company, regularly since 2005. I started working with Seaberg in 2012, so technically about fourteen years.

How did you learn about our company?

Back when I was still apprenticing, we would occasionally use both Armand Lee and Seaberg for certain custom framing projects. So I was already aware of both companies before I started to do conservation and restoration on my own. After I left the Conservation Center to work independently and start my own business, Armand Lee was the first to call me and ask me to work on a project with them.

How would you describe your field of expertise?

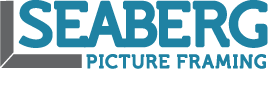

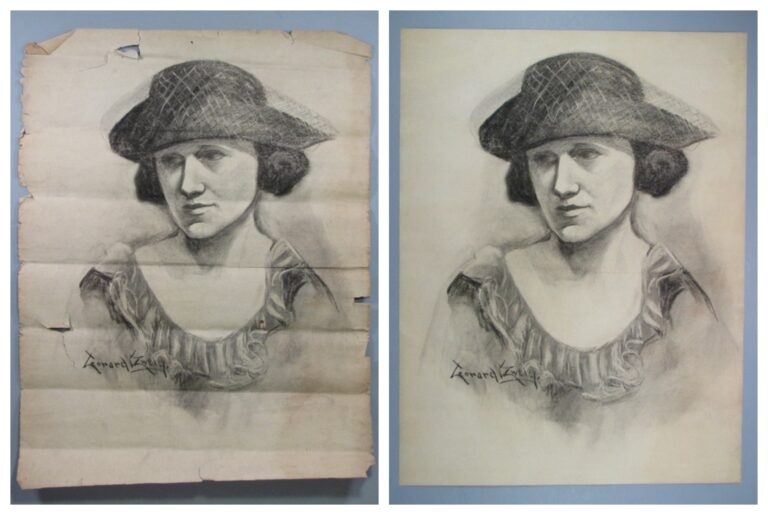

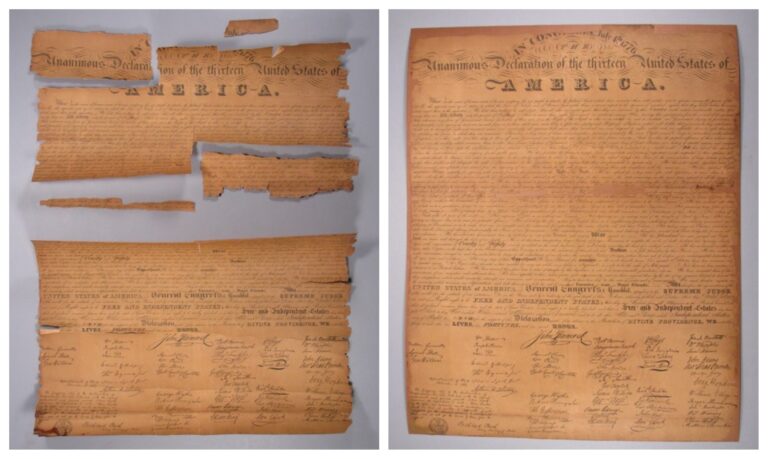

I specialize in restoration and conservation of artworks on paper though I also work on vellum and parchment documents. More specifically I remove staining and discoloration caused by exposure to acidic framing materials. I can also remove water staining, foxing spots, mold, and mildew damage. Separating artwork that has been glued down to backing boards is a frequent necessity.

I’ve also had to repair and stabilize wide varieties of structural damage like creases, tears, holes, missing fragments, and deteriorated paper. Often artwork gets badly undulated and needs to be flattened. Cosmetic retouching is required when an artwork has surface damage of some form or is badly scratched.

Before & After Early 20th Century Charcoal Portrait

What’s the range of projects our companies have worked on together?

A very wide variety of projects and mediums including Asian screens & scrolls, watercolors, mixed media, prints & lithographs, etchings & engravings, posters, 19th century and early 20th-century antique photos, pastel & charcoal drawings, pencil drawings, ink drawings, maps, old documents, and even antique painted folding fans.

What was the first fine art restoration project on which we first collaborated with you?

It was a large 17th-century Japanese screen with scattered splits and fractures, broken hinges, and some worn areas that needed retouching.

What drew you toward art restoration? What kept you interested in this field?

I’ve had artistic leanings from a very early age and I was always drawing or making something, but I first learned about the field of restoration when I was in high school. At that time there was some extensive restoration work being done on the paintings in the Sistine Chapel and I saw a documentary on television about it. I thought it was fascinating and thought what an amazing job that would be. I love history, I love culture, and I love art so the attraction to art restoration seemed natural for me.

What keeps me interested is that I like what I do. I enjoy the restoration process. The process of restoring something torn and stained and battered is very gratifying. I also enjoy working with my clients and seeing the pleasure in their faces when a project is complete and they see the results for the first time. I do my small part in helping to preserve little pieces of history whether it’s part of someone’s family history or something on a bigger scale.

Before & After 1876 Reproduction of the Declaration of Independence

What was the process of apprenticing like? How long did it take you to learn and what was the most challenging thing to master?

I think I was very lucky when I had the opportunity to learn my craft. It was a very intense working environment because we dealt with a lot of insurance claims and that immediately exposes you to an extremely wide range of damage. Every day I worked on artwork that had severe water & flood damage, fire & smoke damage, mold damage, severe structural damage, damage from vandalism, along with the more general problems that come with being badly mishandled over years and being in contact with heavy glues and acidic framing materials.

It was a fantastic learning environment and I loved the challenges. Sometimes unusual situations or objects would come up and we would have to do a bit of troubleshooting to figure out the best way to go about repairing it. I learned that it is important to try to discern the original intent of the artist as much as possible so that you don’t alter the integrity of the artwork. It is also important to learn how to balance the client’s needs along with what is most appropriate for the artwork. With experience, I learned which artworks could be dramatically restored while maintaining the artist’s intent versus which items required a more minimal approach to preserve historical character.

Before & After Signed Lithograph by Henry Moore

Can you recall a unique past project that you previously worked on with us?

I think the most unique project was for an oversized antique map of Paris. It was a 19th-century reproduction that was very large at about 9’ x 11’. The paper had been varnished and it was fully backed with linen which is common with such objects. What made the project unique was that I had to put it back together in a very unconventional way because of circumstances revolving around its eventual installation at the client’s residence. It is an example of having to think out of the box in order to accommodate an unusual situation.

The map was constructed of twenty-four separate panels that all lined up together to comprise the completed map. It was in rough shape and had numerous tears and cracks and scattered missing fragments. There were scattered regions of deterioration from mold and mildew that needed to be consolidated. The linen lining was moldy and no longer fully attached. I had to remove the linen so that I could better clean the map and prepare the surface for the necessary structural repairs. Once the structural repairs were completed and retouched I then attached the appropriate panels together.

What is your favorite past project?

Back in 2006, I worked on an antique photograph of a woman wearing a large black plumed hat. It was extremely brittle and had fragmented into a few dozen pieces of all sizes and shapes. Fortunately, the main part of the image was still in one piece, but there were several interior fractures that were ready to break off into separate fragments at any time. It was completely unstable and was an intense reconstruction effort. The main part of the photo had to be carefully shaved away from the old brittle backboard with a scalpel and each fragment also had to be shaved from the backing board material. This was a very delicate procedure because the photo layer itself was on very thin, fragile paper and the fragments were so brittle.

From that point it was like working on a puzzle – I had to figure out where all the pieces fit together and re-attach them to the main portion of the photograph with tissue mends. When I was able to discern how much of the photo was actually missing I made paper fills to fit into all the missing regions and attached those into place. Then the photograph was lined with thin Japanese tissue and a layer of conservator’s grade mounting tissue so that I could mount the photo onto a new acid-free museum backing board to keep it structurally stable. I had to do a considerable amount of cosmetic retouching to blend in the tear and fracture lines. Then I had to try to interpret what the missing sections were supposed to look like and do some creative drawing and in-painting to get those regions to match the rest of the image as best as possible. It took a long time to do and was a challenge, but it turned out much better than I expected so I was really happy.

Before, In progress, & after Woman in Black Plumed Hat

What advice would you give to artists or those interested in art restoration?

I was very lucky to have the opportunity I did to learn my skills as I got my foot in the door in an unconventional way. I worked in art galleries and also did a lot of picture framing before I got the chance to work with the head paper conservator at the Conservation Center years ago. Openings in this field are somewhat hard to find because the turnover rate is rather low. So I would say the best first step might be to contact a conservation studio near you and ask them if they would take some time to consult with you so that you can get a feel of what might be required of you. You may also want to inquire and consult with someone at the International Preservation Studies Center. Restoration requires a lot of concentration and patience along with a lot of practice. A talent for drawing and painting is an obvious advantage. I do know that my prior experience doing picture framing and working in art galleries turned out to be an asset as I was learning conservation skills.

My advice to artists would simply be to consider the quality of the materials they are using and their potential longevity. Some more modern or unconventional materials may seem interesting to use, but many of these materials do not age well or are difficult to repair if damaged and consequently have a short “lifespan.” If you want your artworks to be enjoyed long into the future use media that age well. Also, sign and title your artwork with stable media like a pencil. Pen and marker can often bleed or fade. Finally sign your artwork, not your mats! The artwork might be able to be saved, but the matting often cannot be repaired.

All projects pictured were restored by Jackleen Leary. Check out more of her work at her site.

Click Here – Contact Seaberg’s Experts with Your Art Restoration Questions